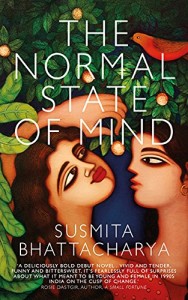

Parthian proudly celebrates their ‘carnival of new voices in independent publishing’, and the jacket from Structo eleven contributor Susmita Bhattacharya’s debut novel promises no less; it dances with verdant greens, bold reds, even a faintly sexual charge between two female figures. Superlative quotes from critics promise beauty, humour, tenderness, love, and friendship, all set against a thrilling backdrop of 1990s Mumbai in political upheaval.

Parthian proudly celebrates their ‘carnival of new voices in independent publishing’, and the jacket from Structo eleven contributor Susmita Bhattacharya’s debut novel promises no less; it dances with verdant greens, bold reds, even a faintly sexual charge between two female figures. Superlative quotes from critics promise beauty, humour, tenderness, love, and friendship, all set against a thrilling backdrop of 1990s Mumbai in political upheaval.

The story, following the changing fortunes of two young women in Mumbai and Calcutta, is no less promising. Dipali is the shy new bride, implausibly happy in her marriage to Sunil, who is bold, smart, funny, and sensitive: the perfect husband. Moushumi knows her own heart, but her conservative family and community forbids her to follow it; she is in love with Jasmine, a rich socialite married to a famous architect, and their affair must remain a secret.

[Moushumi] buried her face in her hands and wept. ‘Mother Superior said to me that I’m not normal. I have gone against God’s ways.’

‘Ignore her,’ Dipali hissed. ‘Who has the right to decide what’s normal? I’m not normal either then. My brother called me a whore. Can anyone define what is normal?’

In the first half of the novel, starting in 1990, Dipali and Moushumi’s lives run in suggestive parallel—the blissfully content domestic life of a ‘normal’ couple set against the clandestine affair of lesbian lovers who have to hide their love from both family and society. A tragic course of events in 1993 bring these two women together in Mumbai and force them to confront the ways society has marginalised them both. Together they find the strength to live life on their own terms.

Bhattacharya writes fondly of the rich detail, linguistic diversity, food, drink, colours, and aromas of her home city of Mumbai:

The street lamps glowed orange and the promenade was busy with people out celebrating. Youngsters and older people alike waved sparklers around, creating light lines in the air. Showers of sparks flared up from tubris, accompanied by laughter and cheers.

Passages like these demonstrate a meticulous recreation of the city, its landmarks, and the mood of a society wrestling with change. There is a lightness, empathy, and humour that sparkles throughout the prose, such as in a humourous scene of elderly women terrified by the installation of new escalators at the train station. It’s easy to see why Parthian has championed this author’s debut; her voice is warm, accessible but unique, offering a refreshing female perspective and experience amidst a crucial moment of political upheaval and social change in India.

Her pared-down style is evocative and suggestive in the short story form, such as in the dark ‘Comfort Food’ in Structo issue eleven, or the epistolary story she contributed to Parthian’s fine Rarebit anthology. But stretched taut over the long course of this novel, the style begins to wear thin. Bhattacharya attempts to capture Dipali’s range of emotions, from her euphoria as a new bride to her grief and eventual recovery; however, the simplistic prose dilutes the emotional impact the reader might experience. In the following scene, Dipali clutches her dead husband’s watch and revisits the sadness, anger, and frustration of the tragic night that changed her life:

She longed to feel Sunil’s touch on her body. His breath in her ear. She covered her face with her hands. The warmth of a loved one in the same bed was what she wanted. That night, she wanted Sunil as she had never wanted him before. But her arms were empty, and the bed was cold.

Scenes progress in this abrupt staccato, making it difficult to empathize. Likewise, characters ‘throw back their heads in laughter’, or their bodies ‘rack with sobs’, and the unreality of their emotional reactions makes it clear that the characters are simply placeholders. Because Dipali and Moushumi’s reactions and emotional states are presented so flatly, nothing feels real or affecting.

These stylistic quibbles are not an insuperable problem; Cynan Jones, another Parthian author, uses blunt, sanded-down prose to incredibly moving effect in The Dig, for example. The problem that undercuts this novel’s ambition and good intentions is the way it unwittingly relies on the same insidious assumptions at the centre of mainstream romantic melodrama: that a woman’s success, happiness, and fulfilment in life directly relate to her success in romantic relationships.

Take the fact that both Dipali and Moushumi are teachers. It is a career that shapes your view of the world and your place in it; you are a role model with a responsibility for the future of others. It can be an all-consuming, frustrating, and immensely tiring job. But apart from being told that Dipali and Moushumi are teachers, we never learn who or what they teach, or how they feel about their roles as educators when they both feel so ‘abnormal’ in their personal lives. What they do seems less important than who they love.

In several instances, the two young women need men to progress the plot. The suave and confident Sunil opens Dipali’s eyes to sexuality and independence, and then the mysterious photographer Gundharv turns up to enable another stage in her life, bringing her out of grief and withdrawal. He also handily takes care of Moushumi’s dilemma by gifting her a job (one completely unrelated to anything we know about her or her character at that point). And this is where the novel falters. The author inserts jibes targeted at the romantic clichés of Bollywood cinema and cheap romantic pulp fiction, but the tropes are used throughout the novel with alarmingly regularity. Dipali and Moushumi are pressed into a situation that forces them to test the assumptions of their patriarchal society, but their route forward is only enabled by men.

— Dan

–

Dan Bradley is a writer, critic, and translator from Japanese. He lives in London.

The Normal State of Mind was published earlier this year by Parthian.