Review: ‘Sitting Ducks’ by Lisa Blower

‘If you’re not angry, you’re not listening’ is the message on the front of Sitting Ducks and it’s hard to disagree. Lisa Blower isn’t alone in using literature to explore post-industrial Britain, but where others may struggle for authenticity, her first novel convincingly captures the world of zero-hours contracts and profiteering landlords.

‘If you’re not angry, you’re not listening’ is the message on the front of Sitting Ducks and it’s hard to disagree. Lisa Blower isn’t alone in using literature to explore post-industrial Britain, but where others may struggle for authenticity, her first novel convincingly captures the world of zero-hours contracts and profiteering landlords.

Stoke-on-Trent is the setting, but the city-region better known as the Potteries is much more than a backdrop, running through the book like the lettering in a stick of rock. Even the title has a double meaning as ‘duck’ is a common term of endearment in Stoke.

The demise of steel production and coal mining hit the city hard and cheap global production of pottery led to the closure of dozens of factories and the loss of tens of thousands of jobs. In the city’s heyday, Potteries-born author Arnold Bennett (Anna of the Five Towns) would take great pride in turning over plates to show his dinner guests the mark of his hometown. Teapots and dinner services are still made with love and craft in north Staffordshire, but on nothing like the scale they once were.

Lisa Blower’s protagonist Josiah ‘Totty’ Minton is one of the many men unable to fill the hole in his pride and his pockets left by the vanished pots and pits. Totty and his mother Constance are struggling to hold onto their house and their hope. Houses have changed hands for a pound in Stoke – sadly, this is not fiction – and Constance battles to hold the family together despite serious illness. Totty cannot find work and represents the generation of men left behind, as jobs migrate to warehouses and call centres. Talking to his son, Joss, he is only articulate in describing his despair. “I was born for summat and I’ll die for nowt cos this world don’t need men like me. Robot does it faster. Computer don’t need paying.”

Lisa Blower has created strong characters and given a timely voice to the legions of people struggling to regain a sense of purpose, pride and community

And men make trouble and join unions too, Totty says. Joss is saddled with the burden of parental expectation, but feels he cannot escape his upbringing despite his talent. He’s the brightest lad in the year but resents being used as a ‘poster boy’ for the downtrodden and when Totty tells him he’s different he replies: “I can’t be. I’d never fucking survive round here if I was.”

Joss has to blend in and that means acceptance of his surroundings. A line of social workers and councillors passes through the Mintons’ lives but never gets to grips with their problems. Malcolm Gandy, the predatory landlord, is always looking for properties to buy and rent and the Mintons can only watch as he snaps up the houses around them. There are no chapters in Sitting Ducks. The author opts instead for rounds, as in boxing, to capture the arguments. In Round 35, Constance describes the long list of neighbours that once surrounded her, now gone forever.

There is a stark message about what has been lost, but if this all sounds too depressing or without hope, it isn’t. Humour is always there (except perhaps for the Lib-Dems following the 2010 election). As Constance observes: “The one with the least votes has become the kingmaker. Nick Clegg could finally spin – “I’m with the band.””

There is tenderness and beauty too, with a wonderful comparison between the delicate handling of fine bone china and Totty as a baby boy. Constance says of Totty’s father: “Then he’d carry them away, like porcelain babes, and hand them over to the dippers who’d plunge them into love once more.”

Characters are summed up with economy and skill. There’s Rhonda, the ex-social worker, who “can fill a phone box with her chub and gristle and ginger ale skin.”

And Frank Blatch’s father: “Gunner in Korea he was, two perforated eardrums. Had no balance after that. Used to keep buckets on the stairs for he when he went up, he’d be that sick.”

Despite moving across the Midlands, Lisa Blower has retained a Bennett-like (Alan rather than Arnold this time) ear for the rhythm of Potteries speech. “She went to Australia: fat as butter, stack of kids, never writes.”

The Potteries dialect is said to be close to Old English and words such as ‘werritin’ (worrying) will have many readers heading for Google, but this isn’t a bad thing in an era of homogenised speech.

I’d like to have heard more from Joss (can he escape his surroundings?) and his imaginative sister Kirty and I can’t help thinking Totty’s temper and diminutive stature would’ve got him into deeper trouble or danger. Sitting Ducks may be too political for a minority of readers but it is the characters’ voices that come through rather than any agenda of the author. A few typos that crept in will be spotted by locals – Wedgwood incorrectly spelt with an extra ‘e’ – but Lisa Blower has created strong characters and given a timely voice to the legions of people struggling to regain a sense of purpose, pride and community.

British politicians have been scratching their heads in recent months and if they really don’t understand the frustration that exists out there, they should read this book.

Failing that they could always help the craftsmen of the Potteries and buy a plate “baked with love” instead.

— Richard

Richard Lakin trained as a chemist and has worked as a policeman on the London Underground, a farm labourer, print journalist and pharmaceutical salesman among other occupations. His short stories and travel writing have won prizes in the Daily Telegraph and Guardian newspapers in the UK and been published extensively in magazines and online. He lives in Staffordshire, England.

His blog can be found at richlakin.wordpress.com

Writing cabanas

Roald Dahl had one. Virginia Woolf had one. Thoreau went to one to live deliberately. Hemingway had one over his garage with a bridge to his bedroom. Now I’m building one too. Sandwiched between the chicken yard and the sheep pen on my friend’s farm, I’m wrapping up the exterior work on an 80 square foot writing cabin. It will have a bed, a desk, and a bookshelf — simple living for weekends. It’s no Walden, but I do hope that the peace and quiet (not counting the crowd and bleats of the barnyard) will help me finish my chapbook projects.

Roald Dahl had one. Virginia Woolf had one. Thoreau went to one to live deliberately. Hemingway had one over his garage with a bridge to his bedroom. Now I’m building one too. Sandwiched between the chicken yard and the sheep pen on my friend’s farm, I’m wrapping up the exterior work on an 80 square foot writing cabin. It will have a bed, a desk, and a bookshelf — simple living for weekends. It’s no Walden, but I do hope that the peace and quiet (not counting the crowd and bleats of the barnyard) will help me finish my chapbook projects.

—Matthew

Review: ‘I Am Because You Are’ edited by Tania Hershman & Pippa Goldschmidt

Last year marked a hundred years since Albert Einstein published forty-six pages that would come to change the course of human history and everything around it. His Special and General Theory heralded a new way of thinking in physics, suggesting as it did that the universe is dynamic, that time is not independent, and that black holes – unfortunately for all who pass them – exist. Since its conception, Einstein’s theory has influenced countless physicists and paved the way for numerous further discoveries. To celebrate the centenary, Freight Books has published a collection of short fiction, poetry and essays edited by Pippa Goldschmidt and Tania Hershman. This is not a physics book. Far from it! But it is a book inspired by physics.

Two people could not be better suited to overseeing such a collection. Goldschmidt, whose books The Falling Sky and The Need for Better Regulation of Outer Space react against some of the most exciting scientific discoveries, has a PhD in astronomy; Hershman, on the other hand, began her working life as a science journalist before publishing two spectacular short story collections, My Mother was an Upright Piano and The White Road. Between them they have produced a collection that is as thought-provoking and inspiring as its subject matter, and which acts as a central hub around which the various pieces expand and contract.

To better introduce new readers, and others who may be put off by the collection’s perceived lofty heights, the editors begin with a welcoming introduction explaining relativity and the importance of Einstein’s most famous work. This, and the short essays which act as interstitials throughout the collection, are pitched so as to appeal to readers regardless of their background. They also serve to obstruct the long-held view (heavily dented by the popularity of shows such as The Infinite Monkey Cage) that between those who practice science and the arts is a never-shrinking gulf.

a collection that is as thought-provoking and inspiring as its subject matter

Happily, though, I Am Because You Are often leaves the reader with questions and astonishment. Contributions to Goldschmidt and Hershman’s bananas universe range from intimate character explorations that tap in to the peculiarity of life on a living space rock, as in Andrew Crumey’s stellar ‘Eclipse’, to the downright, out-and-out, balls-to-the-walls lunacy seen in works like Vanessa Gebbie’s ‘Captain Quantum’s Universal Entertainment’, which features, among other things, Lucille, the Incredible Bearded Shrinking Lady – say no more.

One story that shines out in this diverse and thought-provoking collection is ‘Correspondence’, which captures a snapshot of Einstein at home as his work begins to eclipse his duties as a father and a husband. Another is Goldschmidt’s ‘The Shortest Route on the Map is Not the Quickest’ which, serving as the signal to the collection’s untimely end, sees a Helmand-veteran-turned-London-cabbie and a peculiar P.I. talking around one of Einstein’s most famous two-part statements.

He positioned two fingers someway apart on either side of his cup. “When you do the knowledge you’ve got to learn how to negotiate around that coffee. It’s large, it’s hot and it’s causing a hell of a traffic problem.”

I watched as he traced some imaginary routes on the Formica table top. Some were graceful arcs, others irritable little detours that travelled straight up to the cup and buckled around it at the last minute.

“The sooner you’re warned about the coffee, the better state you’re in. The more possibilities you have and the quicker the detour will be […] City’s a creature in time as well as space.”

More than just another celebration of Einstein’s work, I Am Because You Are attempts to locate the cultural impact of his life’s achievements and reminds us that:

Logic will get you from A to B. Imagination will take you everywhere.

Phil Clement was raised by foxes in the Forest of Dean and currently works in academic publishing as a production editor; neither of these are as glamorous as they sound. He is a regular contributor to the New Welsh Review and Open Pen Magazine, and can be found at https://niagraphils.wordpress.com/

A Bookish Tour of Berlin

We continue our bookish tour around the world. This week, we’re in Berlin with Timothy Kennett.

The many problems of the bookish have been well-documented in textbooks on bibliomania, literary autobiographies, and the kinds of high school fiction in which shy, bespectacled youngsters suffer at the hands of their louder, beefier, and less pimply classmates. I want to suggest a modest addition to this litany.

I should perhaps sketch some necessary contexts. I recently moved from Anglophonic London to multilingual but still resolutely German Berlin, and I suffer from a near-total inability to read texts written in German with more complexity than a café menu. Unfortunately, the majority of bookbuyers in Berlin do not share my affliction, and seem perfectly capable of reading all manner of books – dictionaries, self-help books, Kafka, books about wolves – in German. Or at least, this is what I surmise from the volume of German books on sale everywhere I turn, and from the comparative paucity of English volumes for those of us who suffer in this way.

the majority of bookbuyers in Berlin do not share my affliction, and seem perfectly capable of reading all manner of books – dictionaries, self-help books, Kafka, books about wolves – in German

There are some outlets for the sorry monolinguist: the English-language section in Dussmann, a beautiful English bookshop in Prenzlauer Berg called St George’s, and a couple of other, similar establishments, not to mention serendipitous English texts disguised in Flohmarkts, abandoned on the street, or imported by kind visitors. All of these are near-miraculous, but they don’t address the basic problem of this bookish immigrant: the supply of readable books is dangerously low, and each book is far more expensive than this sad specimen is accustomed to.

I mean expensive not just in terms of euros and cents, although certainly this is the case, but also in terms of everything else. Books have become scarce, and therefore precious. I think of those adventure stories where the young hero or heroine is sequestered away somewhere like Montana in the 19th century and only has three books to read over and over again, becoming gradually more and more obsessed with, say, Paradise Lost or Little Women. Really though, this is just another bookish fantasy: I have not found myself engaging more richly or deeply with the few books I have. I have not fondled every line as I read and re-read it. I have not committed my favourite scenes to memory, nor has my overwhelming sense of camaraderie for, say, David Copperfield, made me feel as if I always had a friend by my side, even when I didn’t.

No, my problems, as with so many of the problems of the bookish, are purely physical. I am hopelessly attached to the material form of the book, even though I increasingly realise that it is hopelessly cumbersome.

I do not feel as if I am any more or less engaged with the written word than I ever was before, but the quality of my engagement has changed. Whereas before I would spend my literary time reading books, reading about books, stacking books with self-satisfaction around my room, alphabetising books, discussing books with friends, dreaming of books that were soon to be bought, browsing for books in voluminous bookshops, displaying books on trains, and in general trying to get through books at a wonderful rate, I now find myself engaging instead in a range of essentially administrative tasks.

Having managed to acquire an actual book, and having enjoyed the feeling of it in my hands, I add it to my nascent collection, which must require more attention than all the items held in the British Museum.

The first step is always planning: deciding which books to buy, and where. Deciding whether to buy the books in England, look for them in Germany, hope they are in the library, or order them over the internet – an option I am increasingly unwilling to take given my ever-shifting address and the worrisome things I have heard about the German postal service. One friend reports that a package she ordered was delivered not to her door or her mailbox or into the bosom of a kindly neighbour or local Paketshop, but to an adjacent outhouse.

Having managed to acquire an actual book, and having enjoyed the feeling of it in my hands, I add it to my nascent collection, which must require more attention than all the items held in the British Museum. The books need carrying around with every move between every temporary sublet, and must be packed in such a way that their corners cannot become dog-eared. They are perhaps too heavy for these bookish arms, which are not used to lifting anything heavier than a hefty hardback, and even that with the comfortable support of an armrest or lap.

The books must be carried on aeroplanes in addition to the U-bahn, because I am leaving Berlin soon, and, in a desperate attempt to avoid having to buy a box, fill it with books, and send it to the UK, I am hoping to transport them book by book on every visit home. Berlin’s airports are well served by Europe’s budget carriers, but Europe’s budget carriers, with their strict hand-luggage restrictions, are not overly welcoming to people who want to carry lots of books around. Innumerable hours are therefore spent weighing options, selecting who to bring with me on the plane and who to leave behind. The same process is repeated for the return journey, and, invariably, having been overtaken with the thrill of easily acquiring more books, my bags are equally laden with new titles as I touch down in Berlin, which does not make the whole process any easier.

I have to leave Berlin in two months, so I suppose something, maybe the copy of a biography of Robert Oppenheimer I have stubbornly failed to read all year, will have to give soon. After that I will move to California, which I suppose will make transporting my books around even more difficult, but should make finding books that aren’t written in German substantially easier. In the meantime, my flatmate, himself Californian, and himself trying to shed some of his acquired bookish detritus, has offered me a number of the books he used to learn German. Naturally, I took them all. Perhaps they will help to resolve my German book problem; perhaps, when I contemplate whether I really need to carry a heavy German-English dictionary and several volumes of German grammatical exercises across an ocean, they will make it worse.

Timothy Kennett lives in Berlin, but not for long. Follow him on Twitter @tpakennett2

Review: ‘The Arrival of Missives’ by Aliya Whitely

The Arrival of Missives could be classed, amongst other things, as a coming-of-age story, a fantasy novel, soft environmentalism, an anti-authoritarian fable and a sci-fi-tinged forbidden love story. This might sound like an unwieldy melange, but Aliya Whitely manages to stitch it together with a strong narrative.

The Arrival of Missives could be classed, amongst other things, as a coming-of-age story, a fantasy novel, soft environmentalism, an anti-authoritarian fable and a sci-fi-tinged forbidden love story. This might sound like an unwieldy melange, but Aliya Whitely manages to stitch it together with a strong narrative.

Set in a small English village in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, the story is told from the viewpoint of Shirley Fearn, a girl about to turn 17, who is infatuated with Mr Miller, her teacher. Mr Miller has returned from the war, and is gossiped about by the local women, who pronounce, ‘He isn’t a real man, of course, not after that injury.’ The nature of Mr Miller’s injury is discovered by Shirley, and it’s more fantastical than anyone could possibly suspect. It would ruin the story somewhat to go into the nature of the injury, but it’s not giving too much away to say that it renders Mr Miller the bearer of a message which concerns Shirley directly. The message warns of a terrible fate which can only be avoided if Shirley gives up her freedom of choice and agrees to follow a path Mr Miller proscribes for her. As Mr Miller tells Shirley:

“I’ve no doubt that what I’m about to say will seem very strange to you, but on such small matters rests the fate of the world.”

Even within the fantastical framework of the rest of the novel, having the stakes so high feels melodramatic and out of place. A slightly less momentous scenario might have served the purposes of the novel better. The agonising choice of whether or not to go against our instinct and follow what appears to be good advice from a person we trust, perhaps even love, is of course a resonant dilemma for many readers. But when the fate of the world gets tossed into the arena, it feels like the author has turned the volume up to 11 for fear that we might not understand the import of the struggle. The themes within the novel are incredibly fertile areas for literature to mine – the pursuit of personal freedom and the development of a sceptical attitude towards traditional figures of authority – but the personal and human struggle of the main character risk being drowned out by the overblown conceit of the story.

It’s interesting that The Arrival of Missives is set during the time that Modernism was starting to become the dominant paradigm in art. Joyce and Woolf write in such a way that the old certainties are discarded in the very writing itself; grand narratives are dead, the time has come for us to retreat from these overarching explanations of life and history, and relentlessly investigate the inside of our own heads. The Arrival of Missives seems to get it topsy-turvy: for the modernists, the world had already ended. The experience of the war meant that traditional sources of authority became deeply suspect. But for Aliya Whitely’s protagonist it’s the prospect of the world being destroyed at some point in the future which leads her to question whether or not she can trust those who claim to know the truth. This isn’t necessarily a criticism of the novel, but rather an observation that the same themes can be explored in a much less Hollywood-esque way.

It’s interesting that The Arrival of Missives is set during the time that Modernism was starting to become the dominant paradigm in art. Joyce and Woolf write in such a way that the old certainties are discarded in the very writing itself; grand narratives are dead, the time has come for us to retreat from these overarching explanations of life and history, and relentlessly investigate the inside of our own heads. The Arrival of Missives seems to get it topsy-turvy: for the modernists, the world had already ended. The experience of the war meant that traditional sources of authority became deeply suspect. But for Aliya Whitely’s protagonist it’s the prospect of the world being destroyed at some point in the future which leads her to question whether or not she can trust those who claim to know the truth. This isn’t necessarily a criticism of the novel, but rather an observation that the same themes can be explored in a much less Hollywood-esque way.

The Arrival of Missives does several things very well. Shirley is an engaging character and the coming-of-age aspect of the story is both emotionally affecting and convincing. A strong sense of place emerges too; the landscape and the social relations of a small English rural community seem by turns to be idyllic and restrictive, which is the perfect setting for Shirley’s existential drama to play out against.

For this reader, however, that drama was a little too heightened, and this tended to overshadow some of the more complex and engaging themes of the book.

Adam Ley-Lange lives and writes in Bath, where he is studying an MA in Creative Writing at Bath Spa University. Along with his partner, he co-runs The Rookery in the Bookery, a website dedicated to the review of literature in translation. You can also find Adam on Twitter @therookbookery.

The Arrival of Missives

by Aliya Whitely

Published by Unsung Stories

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-907389-37-5

ePub ISBN: 978-1-907-389-38-2

Publication date: 09 May 2015

A Bookish Tour of Cambridge

This is the first in our series on bookstores in cities around the world. This week, Heather takes us on a tour of her hometown of Cambridge.

Well-known for its ancient colleges and beautiful parks, Cambridge is actually not known for its great bookshops. I mean, it is by me – I’m one of those people who loves their local Waterstones – but in terms of independent bookshops it doesn’t do very well. Which may just mean that it’s the same as everywhere else at the moment.

After a quick crowdsourcing on Facebook, I was recommended seven bookshops, six of which I visited. Two chains, two indies, two charity shops. The seventh was an indie I didn’t manage to visit but for the sake of a house-buying programme style ‘Wild Card’ I shall discuss it briefly at the end.

Firstly, we have the chain bookstores. Heffers (Blackwell’s) on Trinity Street has a sign that leads you directly to the large children’s section at the back; the shop otherwise carries your standard array of fiction and non-fiction genres, including a second-hand, politics, art, etc. section in the basement. It doesn’t quite match the size or grandeur of the basement which is the Oxford Blackwell’s Norrington Room (sorry Cambridge), but Heffers’ three floors are lovingly laid out, beautiful to browse through and stock an impressively sized board game collection.

Waterstones (Sidney Street) is an impressive four-floors tall (if one should regard a successful chain’s ability to rent nice buildings impressive), which seems pretty standard for a city Waterstones these days. (My small hometown in Wiltshire still has one of those adorable mid-2000s one-floor Waterstones. Ah, the old days.) Again, I wouldn’t necessarily say that Waterstones does anything particularly special. It has a pretty small board game collection, a nicely sized fantasy/sci-fi/graphic novel area, a café on the second floor and regularly hosts book clubs and author events.

who on earth buys a DVD from a charity shop?

Cambridge is home to a plethora of charity shops, including multiple Oxfams. The Oxfam Bookshop on Sidney Street was my first stop, partly on recommendation from a bestie, partly because it was next door to Waterstones. It separates out General Fiction from Literature which upon investigation seems to mean historical and ‘chick-lit'[*] fiction versus classic, poetry and lit crit. But me moaning about current categorisations of literature is probably another article for another day. As well as books, the shop also sells chocolate and DVDs which always makes me wonder who on earth buys a DVD from a charity shop. I mean, aside from the two humans who were browsing it at the time I was visiting (and that one time I regretfully purchased Sleepless in Seattle only to have it break half an hour in).

A children’s and young-adult literature connoisseur myself[**] I was pleased to see that their section included important gems such as Malorie Blackman and Darren Shan as well as contemporary popular YouTuber Zoe Sugg. Glancing at my notes now I see that I scribbled “no HPs????” with literally that many question marks, only to have hastily crossed it out and jotted underneath “HPs&hunger games”, which I guess makes more sense. The shop had sweetly promised “Comics & Graphic Novels!” only to sport a rather sad shelf of falling over graphic novels and a box beneath of sprawling comics.

“What would happen if you set out to write a 20,000 word novella in just one 27 hour session for charity?” I am excited to find out.

I had decided going into this tour that I would buy a book from every indie and charity shop I went to; I then remembered that I am moving out in three months and already have hundreds[***] of books to move, so decided instead to just buy any books I found that looked interesting, to add a little flavour to this already tasty article. On my way out of the bookshop, bereft of purchases, I spotted A Town Called Madness, which has a nice, if clearly amateur, illustration on the front and a blank back cover. An entirely unedited and self-published novel, in the intro author Claire Travers Smith asks, “What would happen if you set out to write a 20,000 word novella in just one 27 hour session for charity?” I am excited to find out.

I will just briefly mention the Oxfam Shop on Burleigh Street as it isn’t purely a bookshop, though it was recommended to me on the basis of the first-floor book collection. In-between ball gowns, old crockery and weirdly specific artwork, the general fiction, genre fiction and non-fiction collection includes: poetry with the sign “BBC Poetry Season: TS Eliot is your winner!”; timely Shakespeare; the book What Men Really Think on a “50p/£1 for three!” shelf; and a foreign language section which included Odysseus by James Joyce – a Finnish translation of the hardest to read book ever? I was sorely tempted (though only for the hipster status it might have afforded me, as I know no Finnish whatsoever).

I was slightly disappointed by The Haunted Bookshop, run by Sarah Key & Phil Salin (St Edward’s Passage), which was the only bookshop I hadn’t been to before, nor had even ever heard of. Comprised of one small front square room, the shop also sells online, where you can browse a fraction of their collection and place orders for current stock. Though understandably small (rent prices in Cambridge are famously outrageous), the bookshop just didn’t have enough of a range or an order to satisfy my browsing, though I did spot a book called Fat Free Cookery which was published in 1958 and included a recipe for “gelatine fish”. At £25 I did not buy it for comic value alone.

I realised I had never read a Wodehouse before and maybe this was the sign I had been waiting for that I should

G. David Bookseller is a favourite amongst locals, having been in Cambridge since 1896[****]. It was recommended to me as “that bookshop that sells antiquarian books and also P.G. Wodehouse”. This led to my second and final purchase of the tour, Jeeves in the Offing, as I realised I had never read a Wodehouse before and maybe this was the sign I had been waiting for that I should. G. David is simply a lovely bookshop, with a few small rooms (including a tiny basement which holds philosophy, science, etc.) carrying general fiction and non-fiction beside the huge collection of second-hand/ collectible/ antiquarian books. I lightly stroked the spine of a very early print run of The Fellowship of the Ring before turning my eyes away, knowing that there was no point in looking at the price.

There was a Christopher Morley quote stuck up on the wall of the antiquarian room, lovingly printed and cut out by hand:

when you sell a man a book

you don’t sell just twelve ounces

of paper and ink and glue

you sell him a whole new life

which I appreciated. I thoroughly look forward to the whole new life a first reading of a Jeeves novel may bring me.

And lastly, I couldn’t write this article without second-hand recommending the following: there apparently exists a warehouse style bookshop called Plurabelle on Coldhams Road where the owner is surprised if you visit, and which, as its opening hours are Monday to Friday 10–4, I never will.

—

*eurgh, sorry humans everywhere

**which really makes me wonder – unlike the superfluous DVD comment – how does one get the job of connoisseur?

***hundreds

****not that I’m suggesting that that’s the reason it’s popular, I don’t think many people round here are 120 years old or anything

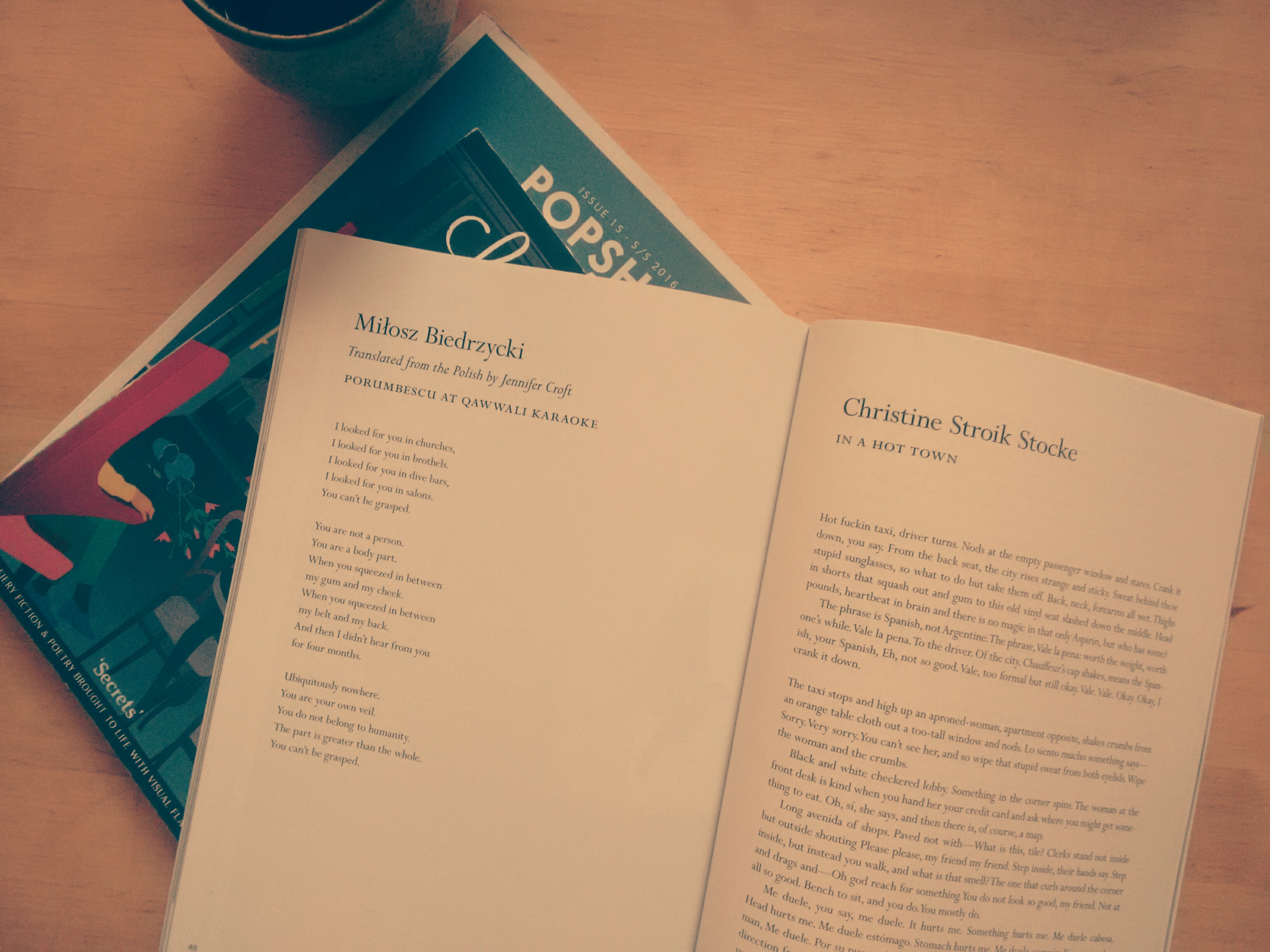

Collaboration with Peer magazine

A little while ago, while in the process of spending far too much money in my favourite magazine shop, Athenaeum Nieuwscentrum in Amsterdam, I picked up a copy of Peer, a brand-new arts magazine based out of the city. It was an impressive first issue.

Cut to a couple of months later, I am delighted share a collaboration with Peer in their second issue, which contains within it a miniature issue of Structo featuring authors and poets from Amsterdam and beyond.

This magazine within a magazine features fiction from Structo alumni Bette Adriaanse and Christine Stroik Stocke, and poetry from Bianca Oana, Judith Kahl, Heath Broussard and Miłosz Biedrzycki, this last a translaion from the Polish by Jennifer Croft.

Peer issue two is available from Athenaeum Nieuwscentrum in Amsterdam, or direct from Peer themselves here.

— Euan

Review: ‘The Foreign Passion’ by Cristian Aliaga

his poems — rarely personal, ferociously political, and consistently uncanny — offer apocalyptic visions of European capitalism as a sober corrective

Review by William Braun.

One may be forgiven for expecting a beast of a different sort from Cristian Aliaga’s The Foreign Passion, a collection of prose poems translated from the Spanish by Ben Bollig and published by Influx Press. A book of a hundred and fifteen pages suggests a full length collection, while the number of pages devoted to translations (thirty-six) appears more worthy of a chapbook. Then there’s the title.

Prospective buyers can decide for themselves whether the lengthy introduction and bilingual accompaniment are essential — while a student of Latin American literature may find the entire volume valuable, a casual reader may not — but the expectations elicited by the title seem deliberate. They position readers as tourists, whose attitude toward the cities and sites of Europe as places of cultural edification Aliaga finds dangerously naïve. Against this mentality, his poems — rarely personal, ferociously political, and consistently uncanny — offer apocalyptic visions of European capitalism as a sober corrective.

This vision is certainly apocalyptic in the surreal sense of the word. Grotesque images swirl through Aliaga’s poems — “global butchers” and “blind jaws” and “teeth polishing dark glass”. More often, however, they are apocalyptic in the etymological sense, insofar as they seek to un-cover the violent machinations beneath Europe’s attractive surfaces. ‘Mechanism of Wealth’, for instance, interrogates an exhibit of Industrial-Revolution-era machines on display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester. Beneath the pristine exterior of these “deities from the tool age”, Aliaga detects the “dead faces and breakable arms” of those who laboured “up to eighteen hours a day” to bolster “someone else’s wealth”, labourers whose existence the exhibit scarcely acknowledges. ‘Other People’s Beauty’, ‘The Photos of the Victims’, and ‘Daily Chore’ indict other institutions for similar atrocities: the British Museum becomes a testament to cultural vandalism, the Imperial War Museum to mass murder, and Harewood House to “precious stones and prejudice”. Colonialism’s legacy scars every monument, every exhibit in this collection.

Coerced by economic necessity or seeking refuge, they become tourists’ invisible doubles, travelling similar routes under vastly different circumstances.

So described, Aliaga’s poems sound like conscientious but unoriginal applications of Walter Benjamin’s observation about cultural documents being documents of barbarism, and it is true that the technique, repeated more often than it is, might risk predictability. But Aliaga’s vision captures more than the barbarism latent in cultural documents. In poem after poem — ‘Face on the Metro’, ‘Password’, ‘The Digital Trace’, ‘Taciturn Professors’ — immigrants emerge from Europe’s shadows, escapees from “the black sites of borders”, victims of police violence, commodities “packaged without knowing their destination”, bodies bought and sold for organs or sex. Coerced by economic necessity or seeking refuge, they become tourists’ invisible doubles, travelling similar routes under vastly different circumstances.

Indeed, their struggles provoke Aliaga’s bitterest (and best) lines. Some are withering observations about the ironies produced by globalization as when, with grim humour, he notes “Immense workshops where docile immigrants package… food for thousands of trusting Europeans who mistrust foreigners”. Others display Aliaga’s ability to twist phrases such that they worm their way into readers’ subconscious, becoming increasingly disturbing the longer they burrow. Consider a line from ‘Taciturn Professors’: “Nothing’s wasted, each bit has a niche on the market.” It seems, at first, a straightforward statement about the efficiency of a free market economy: capitalism on a global scale extracts maximum returns from whatever it consumes. The word ‘niche’, however, provokes unease. It evokes men in trucker hats and extra-large shirts searching flea markets for collectible toys and self-fulfilment, and the dissonance between word and context eventually instigates a disturbing realization: exploitation, for Aliaga, does not originate in any single location or scapegoat. Rather, hydra-like, it spawns from the individual desires and fetishes — the niches — of people who are willing to ignore the suffering of others in their pursuit of happiness. That such lines are memorable for their phrasing testify to Bollig’s skill as a translator: they sound as though they were conceived in English.

those of us privileged enough to travel should do so less as tourists than as pilgrims

Aliaga, in short, proposes a more sober and introspective manner of travel, one attuned to the complex legacies of historical sites and the privilege of travel undertaken for its own sake. As he advises in his final poem, ‘Earn the Path,’ those of us privileged enough to travel should do so less as tourists than as pilgrims, pausing at sites “invisible to those who hurry past toward nothing”, listening to the stories glossed over by museums and travel agencies, the past and present voices of labourers mauled by profit margins. To do otherwise — to obey the foreign passion unquestioningly, to visit Europe’s cities and sites on their own terms — is to overlook what humans like ourselves have suffered and ultimately to be complicit in their erasure.

William Braun lives in St. Paul, Minnesota. A graduate of the Master’s program in English at the University of St. Thomas, he is an adjunct literature and writing instructor at several area universities. His translations have appeared in Exchanges Literary Journal. Follow him on Twitter @blessmekerouac.

The Foreign Passion

by Cristian Aliaga

Translated by Ben Bollig

Published by Influx Press

ISBN: 9781910312209

Publication date: 27 May 2016

Format: Paperback

Reviewers wanted!

We’re looking for reviewers to join our team!

If you love indie presses, works in translation, poetry or short stories, we’d love to hear from you.

Let us know what you enjoy reading and, if you can, provide samples of previous reviews. We’re seeking professional non-biased reviews, but that doesn’t mean they have to be stale. Feel free to send video reviews, audio clips, and other forms conducive to use on the web. Peruse our blog for an idea of the types of books we’ve reviewed in the past.

Email nat@structomagazine.co.uk for more information.

This project-based position isn’t a paid one, but your reviews will be published on our ever-blossoming website. Also, you get to keep the books. Who doesn’t like free books?

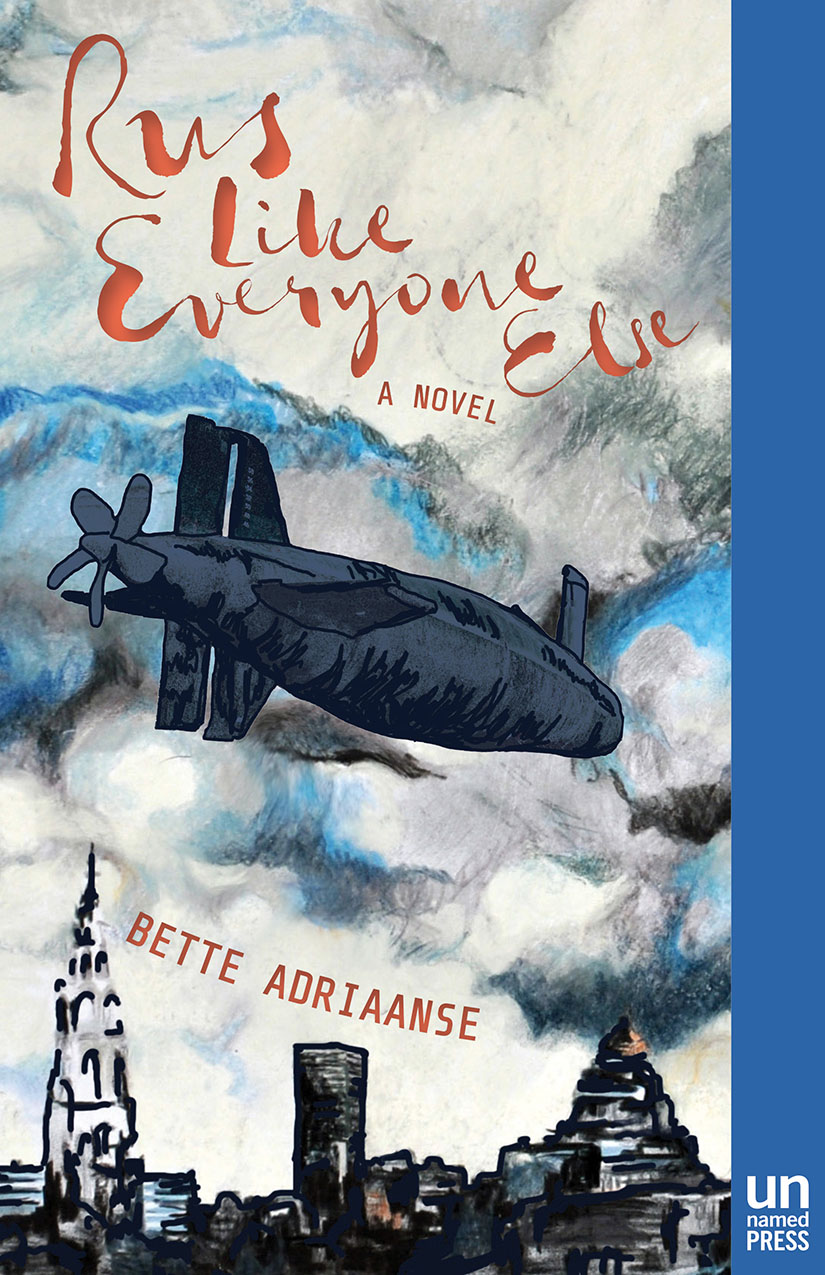

Review: ‘Rus Like Everyone Else’ by Bette Adriaanse

The problem of ‘aboutness’ is that a lot of clarifying attention seemingly has to be paid to plot, or at the very least the author/blurber/reviewer needs to avoid straying too far into abstractedness. We need a few lines about the main character(s) and a taste of what’s going to happen to them. Then, thus grounded, we might be susceptible to a few words like ‘alienation’, ‘community’ or ‘redemption.’

But Rus Like Everyone else doesn’t lend itself easily to this process. For a start, although the book is ostensibly about the eponymous Rus, that ‘Everyone Else’ in the title isn’t there just for show; there’s a huge host of complex characters that have all got complex stuff going on for them. And whenever I tried to summarise Rus’s story or do a quick sketch of the other characters, I couldn’t help but feel like I’d done them all a disservice, as if I’d somehow trivialised them. In fact, I couldn’t help but read my words in the style of that bassoon-voiced guy who features on all the trailers for feel-good Hollywood hits of the summer:

Meet Rus. He’s a twenty-something guy who’s been living in an illegal structure. He’s surviving off the debit card his mother left him when she and her lover ‘followed the birds’. His daily joy is a trip to Starbucks. But Rus is about to get a letter. And that’s going to everything.

Or the following character summations: An old woman who is incredibly invested in a day-time tele-novella. A war veteran convinced that he is being monitored from a white van outside his house who also has trouble deciding whether his green suit and yellow blouse is appropriate attire for a war memorial ceremony. A secretary who wakes one day to find she can no longer see colours. A man in a coma who dreams he is the Queen’s gardener.

Aside from it being difficult to say what the book is about, the main problem was a sudden suspicion of any authority I had to say anything, plus a scepticism about the accuracy and intelligibility of anything I did say. (I realise that in admitting this—as a reviewer—I’ve shot myself in the foot so many times that I’ll never be able to get through airport security unmolested again.)

Then I started to wonder if there wasn’t something in Rus Like Everyone Else that accounted for this feeling. Stay with me here. The nearest I can get to it is to say that reading the book made me feel keenly one of the many weird paradoxes of being human, i.e. that we seem so different and so similar at the same time. We are both deeply strange and deeply familiar to one another. This probably affects how we communicate. That’s not a particularly profound or original statement, but then again, I don’t think that a lot of great literature has to broadcast profound or original statements. Rather, it can remind us of what we already know or feel, and make us feel or know it more intensely. Rus Like Everyone Else made me feel both how separate and how connected people are. It’s short chapters jump between characters, and sometimes some of these characters come together and flourish, escaping from their loneliness; other times they come together and enhance each other’s loneliness; and other times the connections between them are present but ambiguous.

I’m still feeling the after-effects of that heightened awareness as I (try to) write this review. Scientific Equation: I read X so now I’m thinking Y. Layman’s terms: The book did something to my brain. Excuse to the author and this magazine’s editor: The book made me do it. Now I’m thinking that here I am, a stranger, with the job of telling you—another stranger—whether or not you should read this book. But I don’t mind admitting this. I’m honoured and privileged to have read a book that made me feel honest enough with myself to hold my hands up in front of you and say ‘I can’t neatly explain why, but I think you should read this book.’

— Adam

Adam Ley-Lange lives and writes in Edinburgh, producing short fiction and reviews for various publications. Along with his partner he runs The Rookery in The Bookery, a website dedicated to the review of translated fiction.

Rus Like Everyone Else was published by Unnamed Press in November 2015.

Note: A short story by Bette Adriaanse was published in Structo issue eight, and we interviewed her about her début novel here. We ask our book reviewers to be equally critical of books by authors who have appeared in the magazine as books by authors who have not.

Posts pre-April 2014 are here.