Rus and the writing of Bette Adriaanse

We published a story called Rus and the Letter in our eighth issue. It’s a deceptively simple little tale full of well-observed wit from Dutch author and artist Bette Adriaanse. We catch up with Bette just as her first novel, Rus Like Everyone Else, is published by LA-based Unnamed Press.

We published a story called Rus and the Letter in our eighth issue. It’s a deceptively simple little tale full of well-observed wit from Dutch author and artist Bette Adriaanse. We catch up with Bette just as her first novel, Rus Like Everyone Else, is published by LA-based Unnamed Press.

Have you always written and created art in parallel with one another?

Yes. At The Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam I studied at the Image and Language department, and I developed both my writing and my visual work. Now I always describe myself as ‘a writer and an artist’ but actually there are very little boundaries between the two for me. I have a lot of ideas, some work better as a story, others should become drawings, sculptures, or combination.

My novel Rus Like Everyone Else is made up of short scenes. The whole book existed as a sequence of images in my mind. I made a series of drawings that were going to be part of it, but in the end the writing created all the images in the mind of the reader.

It’s good for me to work on my visual art alongside my writing. There’s a Dutch writer who said something like ‘being a writer is like being an opposite athlete’. It is bad for your body, all this sitting and thinking. For drawings and sculptures you also need to concentrate but it is more physical, your hands and your eyes do most of the work.

How did you hear about Structo? Through the Oxford MA?

When I started doing the Master in Creative Writing at Oxford University, I spent a lot of time reading British literary magazines. Structo stood out to me because the writing was of high quality, but it was also very diverse. Structo has an eye for stories that have something new and unusual, but are still good stories that engage the reader. Those kind of stories excite me as a writer.

Where did Rus come from?

Rus is the main character of my first novel Rus Like Everyone Else. He is a young man who has grown up in an illegally built home on the roof of an apartment block. He was home-schooled by his mother, and after she left he lived a quiet, dreamy life, oblivious to the modern city around him, using his mother’s debit card to go to the Starbucks and the supermarket. Then, he receives a tax bill and he wakes up to ‘the real world’, and has to start taking part in it.

The character of Rus originates from a feeling of wonder and bewilderment at everyday life, the feeling of being an outsider. I have always had that feeling, and it means you become extremely aware of what other people are doing, you constantly wonder why they are doing these things, you wonder why you don’t want to do it, and what is expected of you.

In the book I have fun with this. Rus is an outsider and he questions normal events and requirements. When you put a magnifying glass on everyday life, it becomes absurd, and funny.

In the book, I have tried to create a collection of viewpoints on modern life, what we tell ourselves about our society and how to live in it, the ways we comfort ourselves and what we believe is normal and real. There are a lot of things that aren’t real about the real world.

We published a section of Rus Like Everyone Else back in issue eight. Your search for a publisher has not been a typical one—why did you go with Unnamed Press in the end?

When I first set out to find an agent and publisher, I made a list of what the qualities my ideal publisher would have. I was hoping I would end up with an internationally oriented publisher who published high-quality and remarkable fiction, loved my book and would promote it well. Also, it would be good if they were nice people.

Later I realized making this list was a very optimistic move. Eventually I found a great agent who really believed in the book, but it wasn’t easy to find a publisher. The book was difficult to pitch, because it has so many characters, and it takes place in a kind of layered reality. Many publishers were afraid to ‘take the plunge’.

Then came a request from Unnamed Press in LA to read the book. One of their editors had heard me read. It turned out that Unnamed Press is exactly the publisher I was hoping for when I made that list. They publish writers from all over the world. Their list is full of brilliant novels that are in some way different from the rest and capture the time we live in a way that hasn’t been done before, like Escape from Baghdad and Nigerians in Space. They are very thoughtful about every step of the publishing process. The design of Rus Like Everyone Else looks amazing, it suits the content so well. Also, they are nice people. I am very grateful and proud to be one of their authors.

I hear novel number two has been sent to your agent. Can you tell us anything about it?

The new novel is about a man named Louis, who lives in an apartment in London. One evening, a man rings his doorbell, he says he used to live in Louis’ apartment, and would like to have a look around. The man gets injured and has to stay the night, and over the following days, Louis finds himself unable to kick him out. When the man reveals that he believes the apartment should belong to him, a miniature war unfolds in the home.

The visitor finds allies in the neighbours who, as it turns out, never liked Louis, while Louis takes advice from an anarchist lawyer who is specialized in Outer Space Law, and from a shopkeeper who believes you should be loyal to a few but brutal to the rest. Louis tries to find an ally in his illegal cleaning lady, but she turns out to be a very different person than he expected her to be.

The novel is about belonging, inheritance and possession and the stories we tell ourselves about who we are and what we are entitled to. It’s also about what happens when you put two people in a small space, who are each other’s opposites.

What are you working on at the moment?

I am preparing for the promotion tour of Rus Like Everyone Else, which will take place in January. There is actually not much I can do to prepare, but I am going to drive through the Midwest, to cities like Chicago and Minneapolis, and it can get really cold over there so I have been googling things like ‘At what temperature do your eyeballs freeze?’ (They don’t, really.)

Having finished the second book I am now in a very exciting phase, I have time to develop the new ideas that have been popping up in my head over the past years. I’m writing down bits of dialogue, setting up new drawings. It is my favourite part of the process.

–

Find out more about Bette and her writing at her website: www.betteadriaanse.nl

This year’s Pushcart Prize nominations

The annual Pushcart Prize for “poetry, short fiction, essays or literary whatnot” is a standard of the small press scene, and we are very happy to announce this year’s nominations from issues 13 and 14. You can read each one by following the links.

The annual Pushcart Prize for “poetry, short fiction, essays or literary whatnot” is a standard of the small press scene, and we are very happy to announce this year’s nominations from issues 13 and 14. You can read each one by following the links.

From issue 13:

— Appeal by Willa Carroll

— Broadcast of the Foxes by David Hartley

— Dismantling the Cot by Philip Miller

— Zoological Catalogue by Nat Newman

From issue 14:

— At the Airport by Manuel Forcano (translated by Anna Crowe)

— The Ghost of a Highway by David Shieh

Good luck to all!

Ooovre

A recent search through Kickstarter’s literary underbelly turned up a project called ooovre, which promises readers a way to “buy books online from local bookstores”. We thought it sounded interesting, and we thought you might too. Here’s an interview with the project’s founder John Bennett.

Why did you found ooovre?

We founded ooovre because we love books and local bookshops, we believe they’re a vital part of a diverse and plural culture, and we want them to be around in 20 years time.

Can you briefly sum up the basic idea?

At the moment ooovre is what in the start-up business would be called an MVP – it allow users to find and order books from local bookshops using a simple email form – we intend to build a fully functioning back end to this if we raise the money.

Why did you decide to raise funds on Kickstarter rather than go the traditional start-up route?

Traditional start-up wouldn’t work for ooovre because the addressable market isn’t big enough – ooovre is really targeted at 10-20% of real ‘book lovers’, rather than casual buyers. Of course it may appeal to that market over time, but it’s difficult to build a business case that would interest a VC. Also, VC money comes with strings attached, we want to be able to do what’s right for booksellers, not investors.

What makes it different from sites like Hive?

We’re different from Hive because we charge no money for referrals and we don’t sell direct to door. In addition we want local booksellers to become much more involved in the business as soon as possible – it exists to support them, ideally they will have a major stake in the business and will be able to direct how it evolves.

Anything else you’d like to add?

We believe that the race is now on for ‘omni-channel‘ retail in the book business – the question is who gets there first – big online retailers moving into the High Street or local bookshops moving into digital. We believe that the best hope local bookshops have is through collective action. Irrespective of whether or not ooovre is the answer we believe that local booksellers have to something, the clock is ticking now.

–

Kickstarter page here: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/980363115/ooovre-a-better-way-to-buy-books-online

Article by John Bennett about the future of ooovre here: https://medium.com/@

Lonesome Savior: An interview with Matthew Landrum

Readers might recall that our poetry editor Matthew Landrum has a particular interest in the language of the Faroe Islands. With his first chapbook of Faroese translations out now from Coldhub Press, we thought it was a good moment to ask him exactly just…

… how did you end up studying Faroese?

I heard about Faroese through reading Christine De Luca [who we published back in issue 10—Ed.]. Christine writes in Shetlandic Scots which is heavily influenced by the now extinct language Norn which was kissing cousins with Faroese. As you can see, that was a bit of a rabbit hole I fell down. I Googled the Faroes and saw how beautiful they were—all grass clad mountains and sheep. I stumbled across the University of the Faroe Island’s summer institute in Faroese and the idea of attending percolated for five years before I finally made it over there.

When did you come across the work of Agnar Artúvertin?

On my first trip to the islands in 2011, I wrote to the writer’s guild and asked them to get me in touch with one of their members. They sent Agnar. My intention in meeting was just to discuss poetics and talk the writing life but by the end of that first meeting we had agreed to collaborate.

How long have you been working on this project?

It’s funny with poetry and translation—there’s often a lag between a project and publication. Art is long and print is just a bit longer. All of these poems were completed in 2011 and 2012. Agnar quit writing toward the end of 2012 and, without new work to translate, the collaboration dried up. It took a few years after that to order the manuscript, submit the work, get accepted, and go to printing.

Any favourite lines from the collection?

I’ll share my favorite poem, The Little Boy, here. To me, it captures the essence of Artúvertin’s poetic persona with its taciturn language and unflinching acknowledgement of the limitations of human decency.

I’m fucking hungry

a little boy said to me

as I was passing a kindergarten

on my way to the shop.

His mother grabbed him by the collar,

shook him, and yelled

shut your mouth

or I’ll tan your fucking hide.

What could I do?

I kept walking.

What’s next with translation for you?

I’ve usually got a few balls up in the air with translation. Last year I finished translating Faroese poet Jóanes Nielsen’s book Bridges of Hungry Words. So I’m looking for a publisher with that. I’m currently working on some Faroese fiction by Sámal Soll and writing a chapbook of free translations/imitations of Lorca. I’m headed back to the Islands in August to meet with my authors and brush up on my Faroese. I’ll see about more projects after that.

–

You can pick up The Lonesome Savior from New Zealand-based Cold Hub Press. It costs NZ$ 19.95 (€12/US$13) which includes worldwide delivery. You can find out more about Matthew and his writing over at his website or on Twitter.

The view from the top: An interview with issue 14 cover photographer Brooke Hoyer

As periodically seems to be the case, I was re-evaluating my photography at the time. I was in some sort of middle space where I felt like I was shooting to get kudos from people (Facebook likes and such) rather than reacting to what I see and trying to explain my perspective through my images. I live only about 50 miles from the mountain and see it all the time. It had been on my list of things to do and I conceived of the sunrise summit as an excellent photo opportunity. But by the time I got around to climbing the mountain, I had jettisoned the notion of pretty pictures. I had come around to the notion that it was going to be a great experience and if I got some cool shots, great.

The climb itself was an adventure. My friend and I left the trail head just before 1 am and just after we had entered the blast area, my boot soles started de-laminating. We made a series of field repairs that allowed me to continue but the time spent was putting us behind schedule. As the pre-dawn started I left my friend behind and made a push to the summit. I missed the sunrise by about fifteen minutes but the light was still fantastic. Jim, the guy in the “Mind the Gap” shot was already up there and he made an excellent point of perspective in that shot. While I took some photos, mostly I just sat up there and enjoyed the experience of being at the top of an active volcano for the best time of the day. When I finally looked at the photos, I was surprised at how well some had turned out.

Thank you again for sharing the photos under a Creative Commons licence. What made you do that?

I’ve become somewhat obsessed with street photography and was quite enamoured with Thomas Leuthard for a time (still like him but my man crush has worn off). He has a few free ebooks and one is on using Flickr to get your stuff seen. One of his suggestions is to license as Creative Commons so as to allow another avenue for image exposure.

I’ve been taking pictures all my life which means I started off in the darkroom. I almost got a BFA in photography at university but ‘chickened out’ after completing about half the program. I’ve spent the intervening years talking pictures but not practising photography. I’ve had very active pursuits like rock climbing and bike racing but family and then two strokes slowed all that down somewhat. So I pivoted back into photography since I need something to challenge me.

What’s the difference between taking pictures and practising photography?

What I meant is that I just took snapshots. While they were sometimes better than average, I wasn’t thinking so much about what I was trying to say. I went to the Grand Canyon one time. I have rolls of film from that trip and I can’t even look at the shots. There is no artistry. It’s just a bunch of pictures that say, hey, I saw this thing.

Your candid portraits are remarkable. How do you work when doing street photography?

I usually don’t ask (though sometimes I will) and just react to what I’m seeing. For a while I was stuck on the recent street trend of high contrast “graphic” style where the people are more props. I’d been trying to move to a more documentary style that incorporates story telling but also is compositionally simple and striking. I want impact. Robert Frank is my new hero.

–

All photos in this piece are (CC BY): Brooke Hoyer. Find out more about Brooke’s photos here: brhoy.me

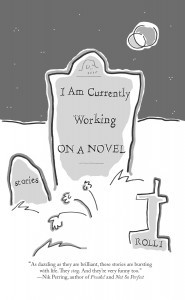

Review: I Am Currently Working on a Novel by Rolli

I have a confession to make. (Another one.) I am reviewing a work of flash fiction, I Am Currently Working on a Novel, by Rolli, who lives in Saskatchewan. And I don’t really know what flash fiction is. Like, I just don’t get it. It’s short, and somehow different from poems, not that I really get poems either. Like condensed, telegraphed stories, stories without characters or plots. So maybe take what I say about Rolli’s flash fiction with a pinch of salt. Or whatever flavouring you’d prefer. I like cayenne pepper.

I have a confession to make. (Another one.) I am reviewing a work of flash fiction, I Am Currently Working on a Novel, by Rolli, who lives in Saskatchewan. And I don’t really know what flash fiction is. Like, I just don’t get it. It’s short, and somehow different from poems, not that I really get poems either. Like condensed, telegraphed stories, stories without characters or plots. So maybe take what I say about Rolli’s flash fiction with a pinch of salt. Or whatever flavouring you’d prefer. I like cayenne pepper.

I Am Currently Working on a Novel is a collection of a lot of stories. I haven’t counted them, but there are a lot of them. Most of the stories are short, but reading them is oddly exhausting. The effect is a bit like listening to a pop album, one of those bubblegum pop CDs that exist only platonically, where all the songs are breathless and pleasurable for two minutes and they all sound the same. Like pop songs, Rolli’s stories have ways of using language that seem wide-eyed and memorable but don’t mean very much when you think about them.

For example, “What keeps so many of us moving, what keeps us breathing, through the week, is the weekend. We form a vision of meaning and float it, over our heads, like helium balloons.”

Now I’m not against pop songs, but I don’t often read them. I certainly don’t read whole albums. To me they seem incoherent, like jelly on paper when I want something crisper and more structured. Maybe sweet potato fries. Cooked with paprika and a dash of cayenne pepper.

Pop albums have this way of structuring themselves that doesn’t necessarily lend itself to appreciation of the whole. The songs reflect each other, with moments of recall, sometimes shared names or places, often the same tone or mood, images and phrases repeated just enough that you notice, but you’re never sure whether it’s some kind of unconscious auto-plagiarism. I want meaning, but it is hard to find amongst the noise.

I should have said though, if Rolli is like an album, it’s more like one of those bubblegum pop LPs made by an indie band—shot through with perversity. Most of the stories in this collection have the same mood: matter of fact about dreamlike occurrence, self-contradictory, with sorrow not far from the surface. The surface itself is shiny, sunny even, and often funny:

I have a scabby tongue. Why, I can’t say. I would benefit from a medical consultation. There is, however, no doctor where I presently live. I presently live in a well.

I was wheeling through the trees, on the wheelchair path, just in awe of the trees, when I realized their new green leaves were actually black and yellow, and were actually bees.

In another story, someone else lives in a well. She is a good example of Rolli’s fairytales turning sad: “When my cakes don’t turn out right, I throw them down the well. Then I hang my head over the edge of the well and my tears fall down into it. Recently my husband complained that the well water has begun to taste suspiciously like tears and cake, and if this doesn’t soon change, he will take my face. The faces of several young women in their prime adorn the kitchen walls.” OK, so, she doesn’t actually live in a well, she just cries in one.

The closest I have come to understanding this sort of thing is Kafka. He has a story of which I am quite fond called ‘The Vulture’. It is only about half a page. It is about a vulture. The vulture is hacking away at a man. The man is not happy about this situation, exactly, but he is bearing it pretty well, all things considered. A second man finds the first man’s passivity shameful and offers to help. This help does not go all that well. I won’t spoil the ending.

Now, it’s not really fair to compare anyone to Kafka. But, Rolli, my apologies, I’m going to anyway:

It seems to me that everything we get in Rolli we could be getting out of Kafka, and we aren’t getting anything new or exciting. Rolli’s situations are absurd, sad, funny, lucid. They end as punch lines or in contradictions. They don’t have Kafka’s tone, though, or his vast depth. They don’t seem like they could be about anything and they don’t seem like they are about everything. To be honest, most of Rolli’s stories don’t seem to be about anything. ‘The Vulture’ or ‘Before the Law’ seem like they could be the most glorious metaphors for all of human life or for whatever else the reader wants. A story of Rolli’s, like ‘Thumbs’, in which a man cuts off his thumbs and then gets fake thumbs, and is happy again, just seems to be about thumbs. Even though the whole story seems like it’s about how desire is perverse and can’t really be satisfied, or some other really universal thing, it still just doesn’t seem to be about anything.

I think the difference is one of style. Kafka, of course, is Kafka. Rolli is very North American, sort of Salinger or something. His writing is a lot flatter. He relies heavily on two techniques. I don’t know if they are representative of flash fiction or not, but they are very representative of Rolli.

Rolli often introduces a short juxtaposing sentence at the end of a paragraph that seems quite unrelated and is designed to inflect everything that proceeded it differently. For e.g.: “I wrote something down on paper and slid it under the door. It said, ‘At the Smoker’s Lounge.’ Janet didn’t think it was funny. She has a degree.” It isn’t clear why this degree thing is relevant, but now it’s inflected our idea of Janet—she’s sort of a snob or something. It’s also a joke: the juxtaposition performing this perverse dream logic. Of course she didn’t think it was funny, no one with a degree finds it funny.

The other thing Rolli does often (and by often I mean in pretty much every story) is delaying the final word of the sentence with an ellipsis or a dash. Usually this delayed word is unexpected. This technique is just another kind of punch line. Here is a passage characteristically dense with these ellipses and dashes: “The precipice. Near … our home. On the edge of town. I should not have thought of it. Yet it remained a thought. On the edge—of the mind. I would be working. Yet thinking…of the precipice. I would be speaking to my wife, and yet thinking. So slowly breathing, sitting, and facing…the bookcase. When I heard footsteps, I reached for a book. She imagined I was reading.”

Here’s an example that’s really like a joke: “The ghost of Winston Churchill was chasing the ghost of a cigar. I was kind of rooting…for the cigar.”

So I think my problem here is that I Am Currently Working on a Novel feels like a collection of hundreds of jokes. And some of them are very funny. I like this one: “I used to bend spoons in the 70s. Now I bend an assortment of other utensils.” I laughed. I like the word “assortment.”

Some of the jokes are less funny. Most of them, in fact. I don’t see this as the collection’s major problem though. It’s not that it’s inconsistent—collections are almost by their nature inconsistent. It’s the opposite; it’s too consistent. It’s all jokes. Sad jokes, funny jokes, weird jokes, boring jokes, like you’d get in any good joke book. But I don’t usually read joke books front to back, like I don’t usually read pop albums. I don’t know how to read them.

–

Tim Kennett is a writer who lives in London. Follow him on Twitter here.

I Am Currently Working on a Novel was published by Tightrope Books.

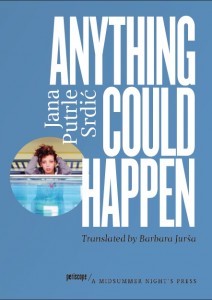

Review: A Midsummer Night’s Press’ Periscope Series

It’s a popular notion in the literary community to say that people don’t read enough literature in translation, especially poetry. It’s one of those opinions that most people nod along with, probably because they don’t read enough translated poetry but ‘have always been meaning to.’ It’s likely that, even in the most well-read of literary circles, most people’s only interaction with poetry in translation are the classics required by grade school and university syllabi—Homer, Ovid, Dante, etc. One major cause of this lies at the root of poetry itself—it can be incredibly difficult to translate something as nuanced and delicately organized as a poem. Poets spend years tweaking even the smallest of details in their poems, details that can be so specific to their language of origin that there is literally no equivalent in the translated language. Thus, poetry in translation is a work of art upon itself, rather than just a copy of the original work in a different language. The translated poem takes on a life of its own, closely related to the original poem but still unique.

It’s a popular notion in the literary community to say that people don’t read enough literature in translation, especially poetry. It’s one of those opinions that most people nod along with, probably because they don’t read enough translated poetry but ‘have always been meaning to.’ It’s likely that, even in the most well-read of literary circles, most people’s only interaction with poetry in translation are the classics required by grade school and university syllabi—Homer, Ovid, Dante, etc. One major cause of this lies at the root of poetry itself—it can be incredibly difficult to translate something as nuanced and delicately organized as a poem. Poets spend years tweaking even the smallest of details in their poems, details that can be so specific to their language of origin that there is literally no equivalent in the translated language. Thus, poetry in translation is a work of art upon itself, rather than just a copy of the original work in a different language. The translated poem takes on a life of its own, closely related to the original poem but still unique.

In A Midsummer Night’s Press’ new series ‘Periscope,’ three international poets publish in English for the first time. Publisher Lawrence Schimel notes that the goal with Periscope is to publish poets that are not only obscure to English-speaking audiences, but are also notably difficult to translate. Schimel says, “translation allows us to see between languages, even if there is not always a straight line of sight, as is often the case when translating poetry, where the translator must often recreate a metaphor or meaning in the target language.” Three books have been published in the series so far, all from female poets in different European countries.

One is None by Katlin Kaldmaa (transl. Miriam McIlfatrick-Ksenofontov)

Prolific Estonian poet and translator Kaldmaa kicks off the series with her collection of poems that reach far and wide while sticking with a few select thematic elements. One of the most obvious trends amongst this collection are Kaldmaa’s ‘My _____ Lover’ series, which feels almost like a Bachelorette-esque reality series cascading through the book. In the first of those, ‘My Bosnian Lover,’ the speaker evokes scenes of romance and passion while weaving a thread about the deep scars of war that still ails Bosnians:

My Bosnian lover

longs for his kin

and is always up at night.

When he walks his footfalls fit

into those of his forerunners.

In another poem of this ilk, ‘My Icelandic Lover,’ the lover in question starts to feel more ethereal, almost “general” as if the speaker isn’t addressing a real lover in this series, but the country from which each lover is purported to be from:

My Icelandic lover

is man, woman, child, creature

from the youngest of places

known to planet and people.

This is a land on the edge

of the one and the other.

The speaker here addresses a deep love for Iceland and its people, history, and culture—reinforced by the use of multiple pronouns in the poem. Both “her” and “him” are used interchangeably when addressing ‘My Icelandic Lover’.

Love itself is also a common thread within ‘One is None,’ finding itself in ten of the sixteen poems in the collection. Some are quite good, like in the poem ‘geography of love:’

but most of all,

yes, most of all i have loved you in this town

where the snow never leaves

where the sun never comes,

and where longing

is the most common feeling.

Others miss the mark a little, as with the last poem in the book, one of the ‘Lover’ series of poems, ‘My Swiss Lover.’ The poem moves between grand statements about Switzerland disguised as comments about the Lover, and overly specific comments that don’t exactly feel married to the first section of the poem.

Nevertheless, Kaldmaa’s writing (and that of her translator) is still excellent in many of the poems, and the thematic framework of the book works well for the most part.

Dissection by Care Santos (transl. Lawrence Schimel)

What initially stands out about the second book in the series by Spanish author Care Santos is how different it is to the Kaldmaa collection. Any notion that translated poetry is any sort of genre is quickly dispelled when reading books as different as these two. Santos bursts through the gates with the first poem in the book, ‘Self Portrait,’ a visceral and self-deprecating look at what’s expected of women in culture:

For many years I’ve felt proud

of knowing how to practice an ancient trade:

offering pleasure

(and at the same time being able to receive it).

While the first book in the series has a playful and often allusive look at sex, ‘Self Portrait’ gets real and gritty from page one.

Much of Santos’ work gets even more detailed and gruesome when speaking about flesh, using titles and terms that might seem more at home in a coroner’s report or scientific research paper than a book of poetry: the second section of the book is entitled “THE DIVISION INTO PARTS OF THE CADAVER OF AN ANIMAL FOR THE EXAMINATION OF ITS NORMAL STRUCTURE OR ORGANIC ALTERATIONS.” The poems themselves tend to have a similar feel, focusing on flesh and bones and the physical properties of humans. In one of the poems that stands out in particular, the speaker is both brutal and beautiful in two simple lines:

For now Oblivion is just a restaurant

where together we feast on my entrails.

As the book nears its end, themes of death and darkness creep into the poems, and the vocabulary becomes a little more abstract. Many of these late poems have a bit of a nihilistic vibe to them, but in the final poem ‘Penitence,’ the speaker devastates in just a few lines:

If you’ve reached here

and you’re still breathing

you’ve already paid for everything you’ve done.

Anything Could Happen by Jana Putrle Srdic (transl. Barbara Jursa)

It’s understandable that, when publishing for the first time in a new language, one would want to provide a sampling of their best work. In the last book published by Periscope so far, Slovenian author Jana Putrle Srdic provides a sampling of poetry from her first three published collections. The goal is to show off Srdic’s range of subject matter and language, which the collection does, but at the expense of a rather disjointed collection as a whole.

Anything Could Happen jumps from theme to theme without much connecting them, aside from the writer’s style and general structural preferences. The author comments on life in the city in ‘The Other Side of Skin,’ and jumps to the writing life in the next, ‘And You Write.’ This isn’t to say these poems aren’t good poems with beautiful writing, like the last two stanzas of ‘The Other Side of Skin:’

The city gives us an infusion of glittering

rhythms and saves us from a sweaty

apartment, flowers in pots that we are quietly dying away,

the city is a recourse of cellophane

and we wait patiently—rabid dogs.

Srdic later shows off some serious poetic ability, like in the poem ‘Fish,’ in which the speaker compares the cleaning of a fish to the organization of one’s home, connecting the two by their roles in the grand order of things.

The collection finishes with a poem that, while different from many in the collection, demonstrates very well the skill that Srdic shows throughout the book. ‘Our Tongues’ is a commentary on the culture of language and translation in the author’s experience of Europe, and she tosses in a sexual metaphor that does as much to evoke that culture as the rest of the poem does altogether:

Still, this language insurmountably

binds us:

this honey-sweet tongue in our mouths

with which we’re licking each other.

As a whole, the Periscope series does a great job at finding and translating poetry that would have otherwise never found its way into the hands of English-language poetry readers. The lessons of the series so far should serve as an example both to future translations by Periscope, and to other English-language publishers translating new work: first, that the right poetry will need to have the right translators that can do the work justice (as far as I can tell, the Periscope series did a fantastic job finding appropriate translators), and second, that individual collections do a better job at teaching new audiences about a poet, rather than a sampling from different collections. The art of writing and ordering a poetry collection says nearly as much about the poet as the poems themselves, and its a disservice to both poet and reader to pick and choose rather than let the reader experience a single collection from a poet. But if A Midsummer Night’s Press and other translation publishers continue to publish poets as good as the three in the Periscope collection, they’ll have done a great things for the global poetry community.

— Spenser Davis

Spenser Davis is a freelance media and culture writer based in Seattle, WA. His work can be found at VICE, Pacific Standard, and The Freelancer. You can read more of his poetry reviews for Structo here.

The first three books in A Midsummer Night’s Press’ Periscope series were published in November 2014.

Ambit Magazine recommends

In the final week of our issue 15 submissions window, we’re sharing literary magazine recommendations from the editors of some of our favourites. Here’s Ambit‘s Briony Bax.

In the final week of our issue 15 submissions window, we’re sharing literary magazine recommendations from the editors of some of our favourites. Here’s Ambit‘s Briony Bax.

“As editor of Ambit Magazine I’m constantly looking at other magazines, sometimes with wonder, sometimes with envy, and sometimes with pure amazement at the proliferation of talent.

“As I lived in the States for 27 years I’m quite partial to a couple of US favourites: Glimmer Train which consistently publishes excellent short stories and never disappoints. It is a good looking book style mag with pictures of the authors from their childhoods which is a nice slant. I also follow The Thing Quarterly, which, while not strictly a magazine, is a piece of art commissioned each quarter and sent out on a subscription basis. What I like about this is it challenges the nature of what is a periodical. And of course McSweeney’s – who in the world of publishing would be caught without one of Dave Eggers’ magazines in their bag?

“In the UK the magazine I read most from cover to cover is The Rialto. It is an institution and I love the size and the design. When it is delivered I take time away from Ambit to look through and read their gossipy editorial and who they are publishing and it always satisfies.”

The 221st (!) issue of Ambit is out now. You can pick up a copy here.

Birkensnake and The White Review recommend

Here are three more literary magazine recommendations from the editors of our favourite magazines. First of all, these two from Birkensnake‘s Joanna Ruocco:

Here are three more literary magazine recommendations from the editors of our favourite magazines. First of all, these two from Birkensnake‘s Joanna Ruocco:

“Xander Marro prints amazing gorgeous zines/books on a risograph featuring stories, comics, drawings, all kinds of awesome stuff. The latest books—Witch Fingers and Trouble—are fabulous. Xander is a phenom in general: artist, performer, puppeteer…

“Also I just got a zine called Macaroni Necklace in the mail. Low-fi and slap dash and inventive and fun.”

The editors of The White Review got also in touch to recommend n+1. We’ve got to agree with this one. A reliably solid magazine. The White Review are currently running a Kickstarter project to support their ongoing work, which we’d recommend checking out.

Firewords Quarterly recommends

In the final week of our current submission call, we are asking the editors of some of our favourite literary magazines to recommend some of their favourites in turn. Next up: Firewords Quarterly‘s Dan Burgess.

In the final week of our current submission call, we are asking the editors of some of our favourite literary magazines to recommend some of their favourites in turn. Next up: Firewords Quarterly‘s Dan Burgess.

“This was a difficult challenge with so many great literary magazines around to choose from, so I decided to go for an international selection. I’ve picked one publication from each country I’ve called home in the recent past.

“Voiceworks — This Australian litmag publishes under 25s, so you really get a taste of Aussie up-and-coming talent. When I lived in Melbourne, I was in this age bracket and tried tirelessly to get published. Alas, it never happened, but I’m still a big fan of this publication which just released its beautiful 100th issue.

“Gutter — A Scottish journal that has been around for a few years now but always feels fresh.

“Carousel — I’ve just moved across the pond to Toronto and this is one of the Canadian magazines that caught my attention. It describes itself as “Hybrid literature for mutant readers” and features all manner of wonderfully bizarre visuals and surprising writing.”

While Firewords recently closed submissions for their fifth issue, at the time of writing copies of issue four are still available. It’s worth picking up; I subscribe to this magazine for good reason.

—Euan

Posts pre-April 2014 are here.